It’s a MONSTER!!

…well, that might be a bit extreme. But the hybridization between Dall’s (Phocoenoides dalli) and Harbour (Phocoena phocoena) porpoises struck me as both rare and strange.

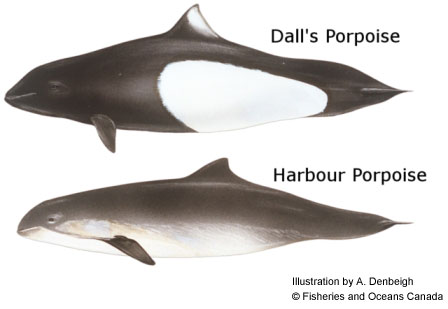

Dall’s and Harbour porpoise morphology. Few good images of Dall’s-Harbour hybrids are freely distributed.

Natural hybridization between wild animals of different taxonomic groups has long been considered rather rare, especially between mammals. Though there have been some reports of mammalian hybrids (especially Grizzly-Polar bear), few have been confirmed (the Grizzly-Polar bear example being one example of a confirmed hybrid). The most obvious reason is incompatibility between chromosomes, but different breeding seasons and mating habits also contribute to the lack of hybridization. However, hybridization could produce individuals which are more suited to their environment, or can inhabit the “border region” between overlapping habitats for which neither parent species is adapted. Perhaps for this reason, hybridization is much more common in plants, and some plants have a recognized “hybrid zone” where ranges of two species overlap. However, almost all offspring of hybridization are sterile, probably due to the difficulties of having two different chromosome numbers; the Lonicera fly is the only example of a distinct animal species that has formed from hybridization.

Canadian researchers used DNA analysis to confirm the tendency of these porpoises to hybridize naturally in 2004, concluding that at least one population hybridizes on a geographically and temporally confined scale. Interestingly, cetaceans as a group have an increased ability to hybridize due to their karyological uniformity; blue and fin whales are the most distantly related mammals to hybridize naturally. Willis et al reported that all Dall’s-Harbour hybrids analyzed had Dall’s porpoise as the mother, and female hybrids were observed to be occasionally fertile, while male hybrids were probably sterile. This hybrid-female fertility was also reported in blue-fin crosses, but has unknown effects on population genetics.

But, if there is little porpoise to hybridization, why does this localized group of Dall’s and Harbour porpoises hybridize? It could be evolutionarily advantageous, as explained above and seen in the example of the Lonicera fly. However, it would seem that with such a localized phenomenon (hybridization in the waters between southern Vancouver Island and the San Juans appears uniquely dense over such a small area, perhaps comprising 1-2% of the area’s porpoise population), some other explanation is warranted. Willis et al suggest that it is perhaps due to environmental factors; there has been an apparent decline in Harbour porpoise numbers locally in the last few decades, and mammalian hybridization is most frequently cited in disturbance events where one population is declining. “A decrease in the availability of conspecific potential mates may increase the cost of choice to individuals, so that some populations, otherwise acting as ‘good species’, begin hybridizing,” notes Willis et al (2004: 832).

An alternative explanation follows from the difference in reproductive strategies of Dall’s versus Harbour porpoises. While Dall’s porpoises routinely are monogamous, producing elaborate displays and then protecting their chosen female from competitors, Harbour porpoises instead devote energy to a promiscuous lifestyle, producing more sperm than other competitors in order to fertilize more females (incidentally, during mating season, Harbour porpoise testicals enlarge to up to 4% of their body mass, one of the largest ratios in the animal kindom…). Therefore, Harbour porpoise promiscuity could be the sole factor behind the propensity of hybridizaiton in this area.

No comment.

-Sarah